In 1922, Italy’s government and King were powerless to bring about change for the struggling nation. With a general strike from the populous looming, the might of Mussolini and his followers rose to the occasion. On October 27, 1922, the Fascist March on Rome was met with zero opposition from the Italian Army or police. Rome fell to the mere threat of violence. Within hours, the King invited Mussolini to Rome to hand him the reigns of the government. Mussolini arrived that evening, disheveled, apologizing for his appearance, claiming he had just come from “the battlefield,” when he had actually just arrived from his headquarters in Milan.[1]

Mussolini implemented his authoritarian government quickly, giving himself full governing power for a full year so as to implement all necessary reforms. In office, his appearance and health diminished. He dedicated all energies into his work, while also taking great pride in living a rigorously simple lifestyle, including a bizarre diet and wardrobe. Though content in marriage, he saw little of his wife and children, yet maintained violent relationships with a number of mistresses. Those who worked with him thought him genius, others thought him mad, but behind the façade was a man who lived in an illusion of who he wanted to be perceived to be- a ruthless yet caring intellectual.[2]

Within a few months of taking over the nation and implementing his policies, people began to settle back into their workspaces. Production output and national pride once again increased. People remained cautiously optimistic that all would be well, as they embraced the myths that fascism had come to save the country from Bolshevist Socialism, and that Mussolini was not only “all powerful and all wise,” but also “God-like, just and merciful, and benevolent.”[3]

Mussolini’s savior-like propaganda reinforced his belief people had no need for understanding the tenants of Fascism, as much as they were to experience Fascism via emotional responses to choreographed techniques that supported a “mystical vision” of the “classic Roman spirit.”[4] His leadership approach, once in power, was quite reserved, even careful. He slowly removed freedoms of the individual to benefit the State, in a way that few would deem repressive. In general, Italians felt the “benefits of Fascism outweighed its disadvantages and faults.”[5]

Over the course of five years, Mussolini abolished free press, opposition parties, and free elections. He restructured the corporate and economic landscape and began indoctrinating the young with Fascist ideology. He supplied Italy with the “peace and quiet, work and calm” it wanted through “love if possible, and with force if necessary.”[6] The more prosperity and peace he provided, the more the Italians loved, cheered, and idolized him. But behind the scenes, Mussolini was a lonely man. Women were to be used; his relationship with his wife, though cordial, was distant; and he had no close friends.[7] Still, he found great joy in spending time with his five children.[8] Though he chose to forgo a salary because he despised the rich, he did manage to enjoy the finer things of life, like flying lessons, driving his sports car, riding his horses, caring for the zoo of animals he possessed, watching films in his personal cinema, and enjoying the sea in his seaside homes.[9]

As I reflect upon Mussolini, I find him to be complex yet shallow. His ideas and drive were tenacious, calculated, and manipulative. His intentional and steadfast commitment to the nation and himself outweighed his commitment to the people; the people were but a means to an end that included power, prestige, position and platform. He punched his working-class ticket by being born to a blacksmith yet chose to live in the world of the intellect, indulging in ideas and a contradictory lifestyle. His keen use of rhetoric and charisma allowed him to strategically control the masses. His ability to demonstrate compassion on cue provided enough credibility that the majority of people followed without question.

Though it would be easy to categorically place “Mussolini” in the “monster of a leader” category, it is just as easy to replace his name in the preceding paragraph with the names of some popular church pastors and “Christian” leaders. Underneath the façade presented to the world lies skewed motives, harsh internal realities, and inflated egos. Is it not just as despicable to use them for perceived good in the Kingdom of God, as it is to use them for evil?

To date, reading about Mussolini’s life has provided a warning and a challenge.

The warning: It actually takes very little to sway masses of people toward a particular position when calculated rhetoric is charismatically presented with a well-structured façade. That holds true regardless of ideological perspective, whether Socialist, Fascist, Democratic, or even Christian.

The challenge: Being a leader that refuses to live and lead from behind a façade is more difficult than living in façade mode. Leading from a place of integrated integrity takes courage, a boatload of hard work, and healthy accountability partners who won’t let you get away with smoke and mirrors bullshit, but rather spurs you on toward wholeness and love.

[1] Christopher Hibbett. Mussolini: The Rise and Fall of Il Duce. (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 1962, 2008) 32-34.

[2] Ibid., 35-39.

[3] Ibid., 41.

[4] Ibid., 42-43.

[5] Ibid., 44-45.

[6] Ibid., 50-51.

[7] Ibid., 59.

[8] Ibid., 57.

[9] Ibid., 43-44.

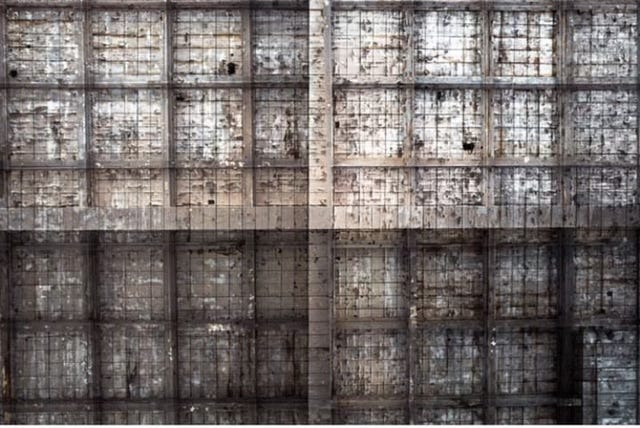

Image: @jonathancastellino on IG. April 3, 2024. Caption- “I wasn’t paying much attention.”